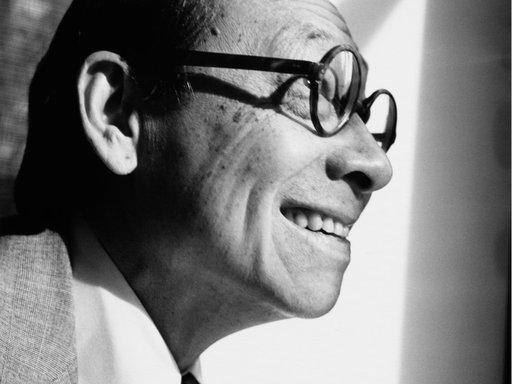

Image above: Ellsworth Kelly with Cité, Quai de la Seine, Paris, 1953. Photo: Sante Forlano, courtesy Ellsworth Kelly Studio.

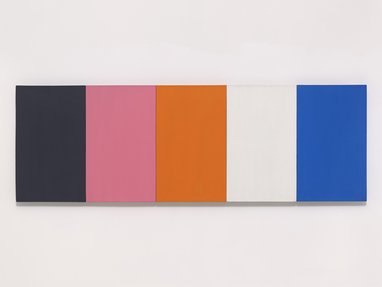

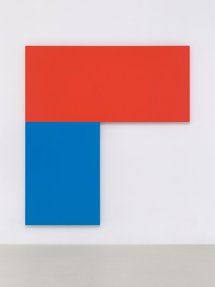

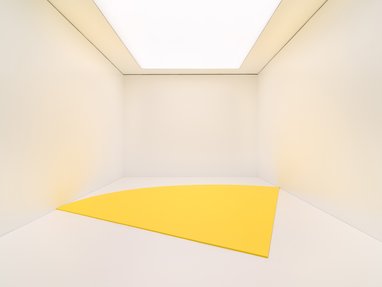

For more than seventy years, American artist Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015) drew inspiration from nature and the world around him to create works of art that would come to define the history of 20th century abstraction. At times associated with Colour Field Painting and Minimalism but never firmly allied with either movement, Kelly developed a precise lexicon of form, line and colour based on acute observations of his immediate environment. He is best known for planes of saturated hues and sharply defined shapes that possess attributes of both painting and sculpture and for engaging the wall and floor in his compositions.

Ellsworth Kelly at 100 is the result of a multiyear collaboration between Qatar Museums, Doha; Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris; and Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland. Envisioned as a presentation that charts Kelly’s artistic development from his earliest experiments through his final paintings, this landmark exhibition highlights critical themes that endured throughout his multifaceted practice. Marking the artist’s centennial, it is the most comprehensive display of Kelly’s work in nearly three decades, featuring painting, sculpture, drawing, collage and photography.

Ellsworth Kelly was born in Newburgh, New York, in 1923. His studies at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn were interrupted when he was drafted into the United States Army during World War II. While in service, he designed propaganda posters and uniform patterns as part of a special camouflage battalion called the Ghost Army and served in major combat operations in Europe. Following the war, Kelly resumed his art education at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.